Help our mission to provide free history education to the world! Please donate and contribute to covering our server costs in 2024. With your support, millions of people learn about history entirely for free every month.

$ 12319 / $ 18000The ancient Egyptians believed that life on earth was only one part of an eternal journey which ended, not in death, but in everlasting joy. When one's body failed, the soul did not die with it but continued on toward an afterlife where one received back all that one had thought lost.

One was born on earth through the benevolence of the gods and the deities known as The Seven Hathors then decreed one's fate after birth; the soul then went on to live as good a life as it could in the body it had been given for a time. When death came, it was only a transition to another realm where, if one were justified by the gods, one would live eternally in a paradise known as The Field of Reeds. The Field of Reeds (sometimes called The Field of Offerings), known to the Egyptians as A'aru, was a mirror image of one's life on earth. The aim of every ancient Egyptian was to make that life worth living eternally and, as far as the records indicate, they did their very best at that.

Advertisement

Egypt has been synonymous with tombs and mummies since the late 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries CE when western explorers, archaeologists, entrepreneurs, showmen, and con men began investigating and exploiting the culture. The first film sensationalizing mummies, Cleopatra's Tomb, was produced in 1899 by George Melies. The film is now lost but, reportedly, told the story of Cleopatra's mummy which was discovered, hacked to pieces, and then revived to wreak havoc on the living. 1911 saw the release of The Mummy by Thanhouser Company in which the mummy of an Egyptian princess is revived through charges of electrical current and, in the end, the scientist who brings her back to life marries her.

The 1922 discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun was world-wide news and the story of The Curse of King Tut which followed after fascinated people as much as the photos of the immense treasure taken from the tomb. Egypt became associated with death in the popular imagination and later films such as The Mummy (1932) capitalized on this interest. In the 1932 film, Boris Karloff plays Imhotep, an ancient priest who was buried alive, as well as the resurrected Imhotep who goes by the name of Ardath Bey. Bey is trying to murder the beautiful Helen Grosvenor (played by Zita Johann) who is the reincarnation of Imhotep's great love, Ankesenamun. In the end, Bey's plans to murder, mummify, and then resurrect Helen as her past-life incarnation of the Egyptian princess are thwarted and Bey is reduced to dust.

AdvertisementThis film's immense box-office success guaranteed sequels which were produced throughout the 1940's (The Mummy's Hand, The Mummy's Tomb, The Mummy's Ghost, and The Mummy's Curse, 1940-1944) spoofed in the 1950's (Abbot and Costello Meet the Mummy, 1955), continued in the 1960's (The Curse of the Mummy's Tomb in `64 and The Mummy's Shroud in `67), and on to the 1971 Blood From the Mummy's Tomb. The mummy horror genre was revived with the remake of The Mummy in 1999 which was just as popular as the 1932 film, inspiring the sequel The Mummy Returns in 2001 and the films on the Scorpion King (2002-2012) which were equally well received. The recent release Gods of Egypt (2015) shifts the focus from mummies and kings to Egyptian gods and the afterlife but still promotes the association of Egypt with death and darkness through its excessively violent plot and depiction of the underworld as the abode of demons.

Mummies, curses, mystical gods and rites have been a staple of popular depictions of Egyptian culture in books as well as film for almost 200 years now all promoting the seemingly self-evident 'fact' that the ancient Egyptians were obsessed with death. This understanding is fueled by the works of early writers on ancient Egypt who misinterpreted the Egyptian's view of eternal life as obsessing over the end of one's time on earth. Even into the 20th century, when scholars had a better understanding of Egyptian culture, the noted historian Edith Hamilton, generally quite reliable, wrote in 1930:

AdvertisementIn Egypt the center of interest was in the dead. Countless numbers of human beings for countless numbers of centuries thought of death as that which was nearest and most familiar to them. [The Egyptians were] wretched people, toiling people, [who] do not play. Nothing like the Greek games is conceivable in Egypt. If fun and sport had played any real part in the Egyptian's lives they would be in the archaeological record in some form for us to see. But the Egyptians did not play. (cited in Nardo, 9)

In fact, there is ample evidence that the Egyptians played a great deal. Sports which were regularly enjoyed in ancient Egypt include hockey, handball, archery, swimming, tug of war, gymnastics, rowing, and a sport known as "water jousting" which was a sea battle played in small boats on the Nile River in which a 'jouster' tried to knock the other jouster out of his boat while a second team member maneuvered the craft. Children were taught to swim at an early age and swimming was among the most popular sports which gave rise to other water games. The board game of Senet was extremely popular, representing one's journey through life to eternity. Music, dance, and carefully choreographed gymnastics were part of the major festivals and one of the chief concepts valued by the Egyptians was gratitude for the life they had been given and everything in it.

The gods were considered one's close friends and benefactors who imbued every day with meaning. Hathor was always close at hand as The Lady of the Sycamore, a tree goddess, who provided shade and comfort but was at the same time presiding over the heavenly Nile River, the Milky Way as a cosmic force and, as Lady of the Necropolis, opened the door for the departed soul to the afterlife. She was also present at every festival, wedding, and funeral as The Lady of Drunkeness who encouraged people to lighten their hearts by drinking beer.

The other gods and goddesses of Egypt are also depicted as intimately concerned with the life and welfare of human beings. During one's earthly journey they provided the living with all of their needs and, after death, they appeared to comfort and guide the soul. Goddesses like Selket, Nephthys, and Qebhet guided and protected the newly arrived souls in the afterlife; Qebhet even brought them cool, refreshing water. Anubis, Thoth, and Osiris brought them to judgment and rewarded or punished them. The popular image of the Egyptians as death obsessed could not be more wrong; if anything, the ancient Egyptians were obsessed with life and living it abundantly. The scholar James F. Romano notes:

AdvertisementIn surveying the evidence that survives from antiquity, we are left with the overall impression that most Egyptians loved life and were willing to overlook its hardships. Indeed, the perfect afterlife was merely an ideal version of their earthly existence. Only the travails and petty annoyances that bothered them in their lifetimes would be missing in the afterlife; all else, they hoped, would be as it was on earth. (cited in Nardo, 9-10)

The Egyptian afterlife was a mirror-image of life on earth. To the Egyptians, their country was the most blessed and perfect world. In ancient Greek literature one finds the famous stories of the Iliad and the Odyssey depicting great battles in a foreign land and adventures on the return journey; but no such works exist in Egyptian literature because they were not that interested in leaving their homes or their land. The Egyptian work Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor cannot be compared with Homer's works as the characters have nothing in common and the themes are completely different. The sailor had no desire for adventure or glory, he was just going about his master's business and, unlike Odysseus, the sailor is not at all tempted by the magical island with all good things on it because he knows that the only things he wants are back home in Egypt.

The Egyptian afterlife was a mirror-image of life on earth. To the Egyptians, their country was the most blessed and perfect world.

Egyptian festivals encouraged living life to its fullest and appreciating the moments one had with family and friends. One's home, however modest, was deeply appreciated and so were the members of one's family and larger community. Pets were loved as dearly by the Egyptians as they are in the present day and were preserved in art works, inscriptions, and in writing, often by name. Since life in ancient Egypt was so highly valued it only makes sense that they would have imagined an afterlife which mirrored it closely.

Death was only a transition, not a completion, and opened the way to the possibility of eternal happiness. When a person died, the soul was thought to be trapped in the body because it was used to this mortal home. Spells and images painted on tomb walls (known as the Coffin Texts, The Pyramid Texts, and The Egyptian Book of the Dead) and amulets attached to the body, were provided to remind the soul of its continued journey and to calm and direct it to leave the body and proceed on.

AdvertisementThe soul would make its way toward the Hall of Truth (also known as The Hall of Two Truths) in the company of Anubis, the guide of the dead, where it would wait in line with others for judgment by Osiris. There are different versions of what would happen next but, in the most popular story, the soul would make the Negative Confessions in front of Osiris, Thoth, Anubis, and the Forty-Two Judges.

The Negative Confessions are a list of 42 sins against one's self, others, or the gods which one could honestly say one had never engaged in. Historian Margaret Bunson notes how "the Confessions were to be recited to establish the moral virtue of the deceased and his or her right to eternal bliss" (187). The Confessions would include statements such as: "I have not stolen, I have not stolen the property of a god, I have not said lies, I have not caused anyone to weep, I have not gossiped, I have not made anyone hungry" and many others. It may seem exceptionally harsh to expect a soul to go through life and never "cause anyone to weep" but it is thought that lines like this one or "I have not made anyone angry" are meant to be understood with qualification; as in "I have not caused anyone to weep unjustly" or "I have not made anyone angry without reason".

After the Negative Confessions were made, Osiris, Thoth, Anubis, and the Forty-Two Judges would confer. If one's confession was found acceptable then the soul would present its heart to Osiris to be weighed in the golden scales against the white feather of truth. If one's heart was found to be lighter than the feather, one moved on to the next phase but, if the heart was heavier, it was thrown to the floor where it was eaten by Ammut "the female devourer of the dead". This resulted in "the Great Death" which was non-existence. There was no 'hell' in the Egyptian afterlife; non-existence was a far worse fate than any kind eternal damnation.

If the soul passed through the Weighing of the Heart it moved on to a path which led to Lily Lake (also known as the Lake of Flowers). There are, again, a number of versions of what could happen on this path where, in some, one finds dangers to be avoided and gods to help and guide while, in others, it is an easy walk down the kind of path one would have known back home. At the shore of Lily Lake the soul would meet the Divine Ferryman, Hraf-hef (He-Who-Looks-Behind-Him) who was perpetually unpleasant. The soul would have to find some way to be courteous to Hraf-hef, no matter what unkind or cruel remarks he made, and show one's self worthy of continuing the journey.

If the soul passed through the Weighing of the Heart it moved on to a path which led to Lily Lake.Having passed this test, the soul was brought across the waters to the Field of Reeds. Here one would find those loved ones who had passed on before, one's favorite dogs or cats, gazelles or monkeys, or whatever cherished pet one had lost. One's home would be there, right down to the lawn the way it had been left, one's favorite tree, even the stream that ran behind the house.

Here one could enjoy an eternity of the life one had left behind on earth in the presence of one's favorite people, animals, and most loved possessions; and all of this in the immediate presence of the gods. Spell 110 of The Egyptian Book of the Dead is to be spoken by the deceased to claim the right to enter this paradise. The 'Lady of the Air' referenced is most likely Ma'at but could be Hathor:

Love History?Sign up for our free weekly email newsletter!

I acquire this field of yours which you love, O Lady of the Air. I eat and carouse in it, I drink and plough in it, I reap in it, I copulate in it, I make love in it, I do not perish in it, for my magic is powerful in it.

Versions of this view changed over time with some details added and others omitted but the near-constant vision was of an afterlife that directly reflected the life one had known on earth. Bunson explains:

Eternity itself was not some vague concept. The Egyptians, pragmatic and determined to have all things explained in concrete terms, believed that they would dwell in paradise in areas graced by lakes and gardens. There they would eat the "cakes of Osiris" and float on the Lake of Flowers. The eternal kingdoms varied according to era and cultic belief, but all were located beside flowing water and blessed with breezes, an attribute deemed necessary for comfort. The Garden of A'aru was one such oasis of eternal bliss. Another was Ma'ati, an eternal land where the deceased buried a flame of fire and a scepter of crystal - rituals whose meanings are lost. The goddess Ma'at, the personification of cosmic order, justice, goodness, and faith was the protector of the deceased in this enchanted realm, called Hehtt in some eras. Only the pure of heart, the uabt, could see Ma'at. (86-87)

Bunson's note on how the view of the afterlife changed according to time and belief is reflected in some visions of the afterlife which deny its permanence and beauty. These interpretations do not belong to any one particular period but seem to crop up periodically throughout Egypt's later history. They are particularly prominent, however, in the period of the Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE) expressed in texts known as The Lay of the Harper (or Songs of the Harper) and Dispute Between a Man and His Ba (soul). The Lay of the Harper is so called because the inscriptions always include an image of a harpist. They are a collection of songs which reflect on death and the meaning of life. Dispute Between a Man and his Ba comes from the collection of texts known as Wisdom Literature which are often skeptical of the afterlife.

Some of the texts which comprise The Lay of the Harper affirm life after death clearly while others question it and some deny it completely. One example from c. 2000 BCE from the stele of Intef reads, in part, "hearts at rest/Hear not the cry of mourners at the tomb/Which have no meaning to the silent dead." In Dispute Between a Man and His Ba, the man complains to his soul that life is misery but he fears death and what awaits him on the other side. In these versions, the afterlife is presented as either a myth people cling to or just as uncertain and tenuous as one's life. Scholar Geraldine Pinch comments:

The soul might experience life in the Field of Reeds, a paradise similar to Egypt, but this was not a permanent state. When the night sun passed on, darkness and death returned. The star-spirits were destroyed at dawn and reborn each night. Even the evil dead, the Enemies of Ra, continuously came back to life like Apophis so that they could be tortured and killed again. (93-94)

In still another version, the justified dead served Ra as the crew of his solar barge as it crossed the night sky and helped defend the sun god from the serpent Apophis. In this version, the just souls are co-workers with the gods in the afterlife who help make the sun rise again for those still on earth. Their friends and relatives who were still living would greet the sunrise with gratitude for their efforts and would think of them every morning. As in all ancient cultures, remembrance of the dead was an important cultural value of the Egyptians and this version of the afterlife reflects that. Even in versions where the soul arrives in paradise it could still be called upon to man The Boat of Millions, the sun barge, to help the gods protect the light from the forces of darkness.

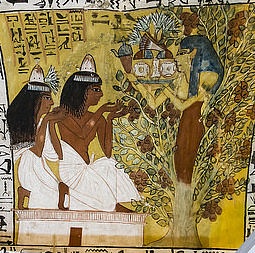

For the greater part of Egypt's history, however, some version of the paradise of the Field of Reeds, reached after a judgment by a powerful god, prevailed. A wall painting from the tomb of the craftsman Sennedjem from the 19th Dynasty (1292-1186 BCE) depicts the soul's journey from earthly life to eternal bliss. Sennedjem is seen meeting the gods who grant him leave to pass on to paradise and is then depicted with his wife, Iyneferti, enjoying their time together in the Field of Reeds where they harvest wheat, go to work, plow their field, and harvest fruit from their trees just as they used to do on the earthly plane. Scholar Clare Gibson writes:

The Field of Reeds was an almost unimaginably ideal version of Egypt where cultivated crops grew to extraordinary heights, trees bore succulent fruit, and where transfigured souls (who all appeared physically perfect and in the prime of life) wanted for nothing in the way of sustenance, luxuries, and even love. (202)

If a soul was not interested in plowing fields or harvesting grains in the afterlife, it could call on a shabti doll to do the work instead. Shabti dolls were funerary figures made of wood, stone, or faience which were placed in the tombs or graves with the dead. In the afterlife it was thought one could call on these shabtis to do one's work while one relaxed and enjoyed one's self. Spell 472 of the Coffin Texts and Spell Six of The Egyptian Book of the Dead both are instructions for the soul to call the shabti to life in the Field of Reeds.

Once the shabti went off to work, the soul could then go back to relaxing beneath a favorite tree with a good book or walk by a pleasant stream with one's dog. The Egyptian afterlife was perfect because the soul was given back everything which had been lost. One's best friend, husband, wife, mother, father, son, daughter, cherished cat or most dearly loved dog were there upon one's arrival or, at least, would be eventually; and there the souls of the dead would live forever in paradise and never have to part again. In all of the ancient world there was never a more comforting afterlife imagined by any other culture.